Who Needs to Pay Fitrana?

Who Is Obliged to Pay Fitrana?

Fitrana is an obligation, but does every Muslim have to pay it? You might be wondering whether you or certain members of your family are required to give to this charity at the end of Ramadan. In this article, we’ll outline exactly who needs to pay Fitrana (Zakat al-Fitr) and who doesn’t. The rules are actually quite simple and meant to ensure that as many people as possible contribute to helping the less fortunate on Eid. By understanding the eligibility criteria, you can make sure you fulfil your duty on behalf of yourself and anyone you’re responsible for.

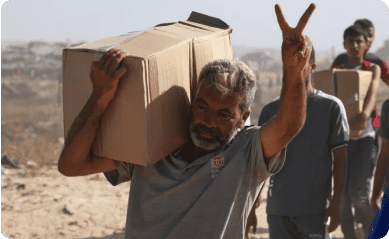

In Islam, every Muslim who has the means to do so is obliged to pay Fitrana for themselves. The criterion for “having the means” is very basic: if on the day of Eid you have more food (or wealth) than you and your family need for that day, then you are considered capable of giving Fitrana. In classical terms, this is often described as having at least one sā‘ of food beyond your own needs. A sā‘, recall, is about 2.5 kg of staple food; basically, if you have enough provisions that a small portion can be shared without causing you hardship, you must share it. Another way to look at it: if you are not classified as poor (destitute) by Islamic standards on that day, you should pay. This means the vast majority of Muslim adults do have to pay Fitrana, because even if you’re not wealthy, as long as you aren’t literally without any food or money, this charity is due. Importantly, the obligation is not limited to those who fasted. Even if someone didn’t fast (for valid reasons like illness) or neglected fasting (though that’s a separate issue), they still owe Fitrana as long as they are Muslim and meet the basic wealth condition. Fitrana is tied to the person, not their fasting record. Additionally, the responsibility extends to the heads of households to cover everyone under their care (more on that below). To summarise: if you’re a Muslim and you can afford your day-to-day meals, you need to pay Fitrana for yourself. It’s as straightforward as that. There’s no complicated nisab threshold like there is for annual Zakat (with calculations for gold, silver, etc.). Even a relatively poor person who perhaps isn’t eligible to pay Zakat on wealth might still have to pay Fitrana because the bar is simply owning some extra food or a small amount of money. It’s a beautiful aspect of Fitrana; it encourages universal participation in charity. That said, those who literally have nothing extra, e.g., a refugee who doesn’t know where their next meal is coming from, are the ones exempt (and indeed should be receiving Fitrana from others).